Krell KSA-50 Amplifier

Among my many life-changing “firsts” I recall—like the first time I had Beef Wellington (September 5, 1972) or received a copy of Meet The Beatles (March 10, 1964)—I will never forget the first time I heard the name “Krell” in a manner unconnected to the film Forbidden Planet. I was attending a minor hi-fi show in Kent, in Southern England, and one of high-end’s odder characters, a fellow US expat named Alex Raffio, came up to me and told me to prepare myself for hearing “the greatest amplifier in the world.”

Among my many life-changing “firsts” I recall—like the first time I had Beef Wellington (September 5, 1972) or received a copy of Meet The Beatles (March 10, 1964)—I will never forget the first time I heard the name “Krell” in a manner unconnected to the film Forbidden Planet. I was attending a minor hi-fi show in Kent, in Southern England, and one of high-end’s odder characters, a fellow US expat named Alex Raffio, came up to me and told me to prepare myself for hearing “the greatest amplifier in the world.”

One day, Alex’s story will be told, in the same tome that will include the tales of John Iverson, Ira Gale, Jim Bongiorno and other world-class audio eccentrics, but that must wait. However “unusual” Alex might have been, his observation was correct. For the next decade or so, as far as the British market was concerned, Krell would own that region’s high-end solid-state market. And that was at a time when the Linn/Naim bloc ruled it with an iron fist.

Ironically, one of the earliest to recognize Krell’s brilliance was John Atkinson, then the editor of Hi-Fi News & Record Review. The irony? He was as responsible as any for encouraging, or at least not containing, the Linn/Naim tyranny. Thus his conversion to true high-end hardware—imported, no less!—was one of the first cracks in that duopoly’s xenophobic control of the UK market. Equally crucial would be his move to the US to edit Stereophile. I tell you this because Krell did not take the US, its home country, by storm from the outset.

Eventually, the impact that Krell’s original, genuine Class-A power amplifiers had on the global high-end scene, outside of its American homeland, would also matter as much in the States. I am in no doubt whatsoever that the UK market discovered Krell before the US market, a belief confirmed by its founder, Dan D’Agostino, even though Krell was, at that time, a fellow traveller of speaker-maker Apogee. When the great history of audio is written, the tale will tell how that pairing—just like Linn/Naim, Audio Research/Magnepan and other great duos—shared their nascent growth. Simply put, the early Krells were the only amps available that could deal with the 1-ohm impedance of the full-range ribbon Apogee speaker.

At the time, Class-A solid-state amplification was nothing new in either the US or the UK, Krell having followed J E Sugden and Mark Levinson. The difference was in the power, because the heat and bulk of Class-A amplifiers restricted them to ratings typically below 25 watts. What Krell did was to apply Class-A topology, with its freedom from transistor-switching distortion, to amplifiers that could keep up with the non-Class-A powerhouses of the day from Threshold, Phase Linear, and Marantz, with ratings typically of 250 watts/channel.

Atkinson, by then a committed Krell user, having fallen in love with the KSA-50 he reviewed in August 1983, immigrated to the US in 1986. In that article, he called the amp “a paradigm shift of the finest kind.” What converted Atkinson, previously a professional bass player, was hearing deep, authentic bass utterly non-existent in systems powered by weedy little British amplifiers. Lower-octave resolution was one of his defining areas in sound reproduction, and the Krell managed it in a way that was alien to the British.

Another critical area was that of soundstage, which the British “didn’t believe in.” In the early 1980s, UK reviewers thought that this was merely a US obsession with no foundation in reality, especially because a revered Linn-Naim setup was totally a “2-D” experience. In Atkinson’s seminal review, he described the soundstage as “wicked big.” Eventually, other UK journalists became Krell fans, including Martin Colloms and Jimmy Hughes. But the US—then in the thrall of The Absolute Sound—would soon realize what it was missing.

[NOTE: If this example of the Brits showing Americans what they had right under their noses sounds a bit presumptuous, please remember that the British played almost as big a part in reviving the then-moribund genre of the blues as did our own Paul Butterfield, Canned Heat and John Hammond, while the Beatles probably did more in their early days to glorify Motown than Berry Gordy ever could have dreamed. Alas, the reverse doesn’t work: The British are perhaps too jaded to realize what they have, so Americans reminding them that they once possessed the world’s finest postal system, produced the greatest affordable sports cars, etc., has no impact.]

Whatever the reasons for Krell’s slow start in the US and its rapid rise in the UK, it was the company’s third amplifier—the aforementioned KSA-50—that made Krell accessible to a wider number of listeners than those who could afford Krell’s KSA-100, let alone its KMA-200 monoblocks. Recently, I was able to spend a few weeks with an as-new KSA-50 acquired by a friend. He invested the same amount in a full restoration that he paid for the unit. The resultant performance reinforced the notion that we haven’t progressed very far in three decades.

Whatever the reasons for Krell’s slow start in the US and its rapid rise in the UK, it was the company’s third amplifier—the aforementioned KSA-50—that made Krell accessible to a wider number of listeners than those who could afford Krell’s KSA-100, let alone its KMA-200 monoblocks. Recently, I was able to spend a few weeks with an as-new KSA-50 acquired by a friend. He invested the same amount in a full restoration that he paid for the unit. The resultant performance reinforced the notion that we haven’t progressed very far in three decades.

My fellow “Saturday Morning Sad Bastard” Jim Creed found the KSA-50 for £600 ($960) on eBay, but when it arrived, we were in for a shock. Much of the original hardware—fuse holders, original terminals, etc.—was missing, and the innards had been tampered with in a manner that strayed so far from the original spec that it needed a complete overhaul.

Checking the serial number, the importer realized that this exact unit had been owned by a notoriously weird British reviewer—one of those benighted souls who bought into the BS of employing such psycho-tweaks as sticking foils and magnetized screws to the amp. It is to the credit of both Krell and the importer that they were able to source every single part to undo the damage.

Presented with a now-pristine example of the Krell, I inserted it into a system consisting of an SME turntable with a 3009 tonearm and vintage Supex cartridge, my oldest CD player (six years younger than the Krell), a circa-2010 Audio Research Ref 5 preamp, and Wilson Sophia 3 speakers. The KSA-50 was right at home, reminding me that back in the day audiophiles like Atkinson often paired Krell amps with Audio Research tube preamps.

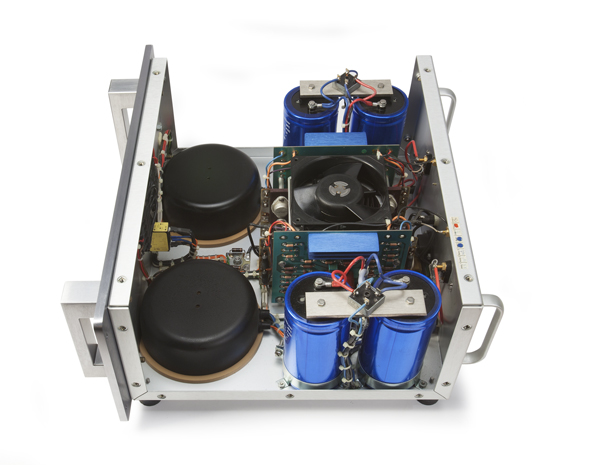

Aesthetically, the KSA-50 is an amp of the “functional” school. Though beautifully made and featuring nice details like a brass name-plaque hand-engraved with a pantograph, it remains a utilitarian amplifier. The front panel comprises simply an on/off switch and an LED to indicate when the power is on. Inside are hefty, potted toroidal transformers and massive capacitors the size of beer cans that flank a large fan to keep this true Class-A beast cool. Its rear-panel fittings are suitably robust.

Although I tried the KSA-50 with current speakers, I couldn’t resist unearthing my cherished Scintillas (a superb modern facsimile is offered by Australia’s Apogee Acoustics, www.apogeeacoustics.com). These speakers are probably best fed by the KSA-100 as a minimum, but, as I am no headbanger, the KSA-50 was more than ample.

Firing up the Apogees, with vintage Krell-power, is a near-religious experience for me, because many years ago this pairing introduced me to the most elevated reaches of high-end performance. To hear that the duo is still formidable 30 years later is as revelatory as my initial exposure, in that the experience is an indictment of all that has happened since: The combination would still earn a 5-star rating today from any listener who is free of prejudice.

As Atkinson noted with utter clarity and precision, the bass is fluid, deep and natural. Inappropriately, given audio snobbery’s still-dominant preference for jazz and classical as the most legitimate arbiters of a system’s worth, I played what I consider to be some of the most seductive, impressive drum sounds of the past 50 years: glam rock from the likes of The Glitter Band, Mud and other trashy but fun pop music of the 1970s. The impact was palpable. And turning to the easier-to-drive Sophias, it was enough to create those sensations that home cinema users experience with powered, vibrating seating—only my chair is conventional and the floor is a 3-foot thick layer of concrete on terra firma. The smallest Krell can cause just about any speaker to move a lot of air.

For the luscious, fluid decay that endears listeners to Class-A performance as much as amps at the sweet top-end, I wallowed in the thunderous double drum kicks and powerful electric bass on “Rock’n’Roll Part II.” This appeared in the cavernous soundstage that paved John Atkinson’s road to Damascus so many years ago. The band’s claps and “hey-hey” chorus stand proudly stage right; the sizzling fuzz guitar stage left.

For the luscious, fluid decay that endears listeners to Class-A performance as much as amps at the sweet top-end, I wallowed in the thunderous double drum kicks and powerful electric bass on “Rock’n’Roll Part II.” This appeared in the cavernous soundstage that paved John Atkinson’s road to Damascus so many years ago. The band’s claps and “hey-hey” chorus stand proudly stage right; the sizzling fuzz guitar stage left.

Nothing about the Krell KSA-50 sounds “vintage” in any way. It possesses all of the qualities that we demand in modern equipment, including speed and attack, clarity and transparency, and—if not so much with the Scintillas—a sense of limitless power and unharnessed dynamic contrasts.

Alas, Jim sold the KSA-50 to a lucky swine who paid him £1,500 ($2,400) for his fully restored example. The original 1983 price was $1,800. Even today, the Krell KSA-50 behaves like a current $5,000 solid-state amplifier of universally recognized pedigree. And $5,000 just happens to be the current equivalent of $1,800 in 1983. So if you come across a KSA-50 in working order for under $2,500, grab it. At the very least, it will heat a small room. -Ken Kessler