Audio Research SP-11 preamplifier

Residing at the top of the heap for at least three decades, Audio Research Corporation preamplifiers are almost default purchases for certain types of tube lovers. ARC preamps are adventurous in their technology yet conservative in execution, so they appeal to audiophiles who like to minimize risks. They’re perfect for listeners who want state-of-the-art sound, while knowing that the maker will still be in business at the end of the listening session. And the unit won’t self-immolate.

Residing at the top of the heap for at least three decades, Audio Research Corporation preamplifiers are almost default purchases for certain types of tube lovers. ARC preamps are adventurous in their technology yet conservative in execution, so they appeal to audiophiles who like to minimize risks. They’re perfect for listeners who want state-of-the-art sound, while knowing that the maker will still be in business at the end of the listening session. And the unit won’t self-immolate.

Such “steadiness” wasn’t always so, as owners of the most important in the SP series, the SP-6, will recall. That preamp went through so many revisions that it became a totem, almost a stand-up comedian’s joke, for high-end instability (commercial, I hasten to add, not electrical). By the time the SP-11 arrived, however, Audio Research was in possession of almost Mercedes-Benz-like gravitas. With today’s Reference models, including the current REF 5 SE and REF 10, ARC purchases are no-brainers.

When the SP-6 arrived in 1978, Audio Research had already earned a place at the front rank of high-end manufacturers—remarkable when you consider that the company was only eight years old. Founder William Z. Johnson’s company made a rapid transition from modifier of Dynaco units to a distinctive brand with its own circuits and its own look; the earliest preamps actually shared faceplates and chassis with Dynacos. The SP-6 marked a big break from modded Dynas, while the SP-10 of 1982 introduced two-chassis topology with separate power supplies.

In October 1985, ARC unveiled the SP-11 at the price of $4,900, which signified another evolutionary step from its all-tube forebears. (Note that the price is equivalent to $10,600 in today’s money, pegging it not far off the price of a REF 5 SE.) This unit was a hybrid, foreshadowing the mature, apolitical and now fairly standard practice of exploiting the best of both worlds. And while I’m aware that there are cultists who would happily debate into the wee hours the merits or demerits of tube versus solid-state rectification, I am not one of them. I’m more concerned with the end than the means.

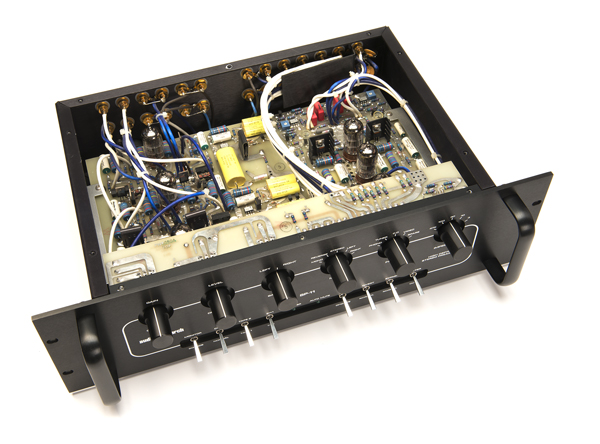

For the SP-11, ARC devised a preamp in which every active stage used a triode tube and a FET; the total complement was six 6DJ8s/ECC88s. The resultant marriage was the blessed mix of valve sound with solid-state noiselessness and distortion that’s impressive even by 2013 standards. Indeed, everything about the SP-11 will allow anachrophiles to insert it into any system you can put together today, with one exception: It predates our current fetish for fully balanced operation, so it has no XLR outputs.

For the SP-11, ARC devised a preamp in which every active stage used a triode tube and a FET; the total complement was six 6DJ8s/ECC88s. The resultant marriage was the blessed mix of valve sound with solid-state noiselessness and distortion that’s impressive even by 2013 standards. Indeed, everything about the SP-11 will allow anachrophiles to insert it into any system you can put together today, with one exception: It predates our current fetish for fully balanced operation, so it has no XLR outputs.

That, however, is as moot a condition as all-tube versus hybrid, and there are plenty of products on the market today without the balanced option—including a few from ARC itself. I certainly wouldn’t let it preclude the acquisition of a mint SP-11 if one were to come my way. (Indeed, I’d love to hear TONE publisher Jeff Dorgay’s SP-11 side-by-side with a REF 5 SE.) And a mint one has to be worth $4,000 of anyone’s hard-earned pay.

Just look at the faceplate: It gives you everything you could want in a full-function control unit, and then some. Like a precious few tweaky units out there, the SP-11 provided separate level and gain controls, which allowed ultra-fine tuning of the volume setting to suit the dynamics of the source. This also prevented overload in a unit, which launched during the first two years of the existence of CDs, while still showcasing LP playback—and many were the jolts when switching from one to the other without adjusting the gain, before everyone got used to the higher output of CDs.

One soon learned how to accommodate sources of wildly differing output, how to exploit the two controls for the lowering of background noise levels and other stages of flexibility not seen in preamps prior to more recent models that allow users to pre-set the levels for individual sources, such as the REF 10, assorted examples from McIntosh and others with on-board microprocessors. With the SP-11, one set the general volume with the gain and fine-tuned it on an as-needed basis with the level control. Both controls employed 32 detent potentiometers.

Its five inputs were labelled phono, tuner, CD, video and spare, while its birth in a transitional era is revealed by a separate rotary with five impedance settings for phono, and another for mono/stereo/reverse/left-only and right-only. Further control beyond the minimalism of contemporary rivals from, say, the British included a row of toggles selecting tape monitoring, tape copy, choice of either of two decks for playback, dubbing in both directions, mute, bypass, polarity inversion and the insertion of a subsonic phono filter. Use of the bypass switch avoided all circuitry except gain, volume control and output buffering. It also deactivated the balance control, a rotary positioned between level and source select.

At the back, as still practiced by ARC, are rows of gilded RCA phono sockets, seven pairs for sources including the tape decks, and six pairs for the two main outputs and tape-record connections. The identically sized power supply provided on/off and activating or switching off of the four auxiliary sockets on the back (three switched and one un-switched). This would have probably been blanked off in export markets, and I suspect most hardcore audiophiles in the United States would have avoided their use on purist grounds. But the convenience was undeniable, especially for single-switch power-on operation.

At the back, as still practiced by ARC, are rows of gilded RCA phono sockets, seven pairs for sources including the tape decks, and six pairs for the two main outputs and tape-record connections. The identically sized power supply provided on/off and activating or switching off of the four auxiliary sockets on the back (three switched and one un-switched). This would have probably been blanked off in export markets, and I suspect most hardcore audiophiles in the United States would have avoided their use on purist grounds. But the convenience was undeniable, especially for single-switch power-on operation.

Also still employed by ARC is a warm-up period from switch-on, so one need never suffer nasty bangs—and as this was likely to be used with big power amplifiers, it’s a precaution worth applauding. What was notorious about the SP-11, despite its hybrid DNA, was a lengthy warm-up period, needing a good 15 to 30 minutes to sound good, and a few hours to sound its best. It always reminded me of a great red wine, one that didn’t truly reach its drinkable best (from opening) until an hour or two had passed. And, yes, I know that there are those who will argue that the only reason wine tastes better at the end of the meal is because you’ve had more to drink than when you started. As one with the willpower to decant my reds three hours before drinking, I know that’s not the case.

While Dorgay will insert into his own hands-on experience with a mint SP-11 in a 2013 context (see “Additional Listening” below), I am content to recall that it sounded less warm than the SP-10, and less tube-y, which is as it should be. Equally, the SP-11 would in no way be mistaken for a solid-state preamplifier, yet it offered the precision, silences and precise bass attributed to transistor control units. I also recall that the phonostage was an utter delight, especially with MCs of relatively high output that could exploit its 47k-ohm setting, and work well enough with its 76 dB of gain. It was and is a magnificent device, an all-time great.

ARC’s Dave Gordon tells TONE, “Terry Dorn and I are guessing that we produced around 3,000 SP-11s, totalling the original and the Mk II together.” And to wind up collectors, he adds, “Of those, we produced 100 champagne gold Mk IIs exclusively for our distributor in Taiwan.” When the SP-11 in Mk II form reached the end of its production, the retail price had only ascended to $5,995.

Dave also noted, “I think it was pretty unusual to see a tube preamp with a phono bandwidth of 100k and a linestage bandwidth of over 200k in 1985.” Hear, hear. -Ken Kessler

By Jeff Dorgay

I agree wholeheartedly with Mr. Kessler that a mint SP-11 is not at all out of place in a modern system today, and he’s spot on for the price of a mint unit. Fortunately, a call to my good friend Jonathan Spelt at Ultra Fidelis, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, yielded the one you see in this article for slightly less. It even included the factory’s original, dual-box packaging—essential if you are paying top dollar.

In the context of a six-figure system, the SP-11 (mine is a Mk II version) holds its own with the REF 5 SE and REF Phono 2 SE that I use as daily reference units. Granted, the newer models offer up more frequency extension, dynamic slam, and a bit more inner detail, but the vintage pre is so damn good in every way, I could easily live with an SP-11 and ignore what I’m missing. A little help from Kevin Deal at Upscale Audio resulted in a great set of NOS tubes, taking my SP-11 to an even higher level.

And the phonostage is fantastic. As more and more rack space seems requisite these days, it’s wonderful to revisit this concept of a great linestage and phonostage all in one chassis, much to the chagrin of the wire barons. I defy you to find anything this good built new today for anywhere near this price.